Daniela Salgado Cofré

Assistant Professor of Design at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, in Chile. Doctoral candidate at the Faculté d'architecture de l'Université libre de Bruxelles.

[online] www.atelier-do.cl

Estelle Vanwambeke

Design Researcher, Professor at the Académie Royale des Beaux Arts de Bruxelles.

[online] www.estellevanwambeke.com

Abstract

By reflecting on the growing vulnerability of living conditions in the context of overproduction and overconsumption in the Anthropocene, this article presents various visions that claim for transitioning design towards alternative models of conception and production guided by an ethic of care. For this, it revisits crafts in its relational approach to production, that is to say, as a system of designing and making that values the territories, identities, social ties, resources, and techniques attached to it.

Résumé

En réfléchissant sur la vulnérabilité grandissante des conditions de vie dans le contexte de surproduction et surconsommation posé par l'Anthropocène, cet article présente différentes visions plaidant pour une transition vers des modèles alternatifs de conception et production guidés par une éthique du care. Il s'intéresse singulièrement à l'artisanat en tant que système de conception et production qui valorise les territoires, les identités, les liens sociaux, les ressources et les techniques qui y sont rattachés.

Introduction

The growing vulnerable social and environmental context that characterises life in the Anthropocene raises awareness about how intertwined the conditions of humans and other species existences are, and the proportional need to design and build a society based on the recognition of our collective interdependence. By engaging in these reflections from a design perspective, this article consists of two parts: the first part examines various visions, especially from the Global South, that advocate for a transition in design and production process based on recognising human and non-human interdependency in life and death, and guided by an ethic of care. The second part of the paper revisits crafts as a system of production that values the territories, identities, social ties, resources, and techniques attached to it. From design researches conducted by the two authors in Chile and Guatemala, it analyses how their practices remain resilient, resistant and iterative when facing global production scenarios. Lastly, this proposition sheds light on the singularity of craftsmanship as an intrinsically 'relational' mode that unifies life conditions and production, that allows to think about a 'relationality' in design and to imagine inventive economic and social relations, capable of restoring social and ecological links in a damaged world, by favouring interdependence rather than interchangeability. By giving insights on how crafts relationality works, we expect to draw less travelled roads for present and future design practices that replace mass industrial production and predatory exploitation.

1. Putting care back at the heart of design and production

1.1 Reversing the mass production of vulnerability in the Anthropocene

As insufficient as happens to be the recent worldwide use of the term Anthropocene to name the new planetary age we are facing – particularly to assign fair historical responsibilities between richest and poorest countries – it is effective to alerting humanity to the scale of the devastating effects of predatory anthropization on the world's ecosystems, and to the consequent scale of action needed. Most importantly, it shows how tied are human and other species together in the shared scenario of growing vulnerabilities in a damaged world. Paradoxically, in trying to free itself from nature in its quest for progress, humankind has reinforced its dependence on other living beings for its survival.

Indeed, the modern idea of progress and development supported by a global economic system requires continuous and unlimited growth in manufacture and consumption. However, to achieve this goal and obtain surplus, industrial and mass production – that today operates on a planetary scale – requires the over exploitation of people, materials, and ecosystems. In fact, the claim to productivity and profit from the economic sphere does not take into consideration its double dependence on ecosystems exploitation on the first part, and on underpaid workforce, mainly handled by women, working class members and racialized persons in most occidental countries1. The Anthropocene consequently leans on capitalist, patriarchal and racist fundamentals which need to be deconstructed.

Regarding capitalist industrial production and overconsumption – in which design has a major role to play – different positions have raised the need for radical changes or transitions towards caring modes of production that consider a respectful interaction between ecosystems and humans within what world-ecology theorists call the web of life2.

One of these expressions is degrowth, which promotes the drastic reduction or downscaling of our production and consumption, considering that the environmental deterioration lies in the overexploitation of resources and excessive accumulation. The notion of degrowth was inspired by some thinkers and intellectuals who criticised modern institutions and the capitalist system of growth and development, like the philosopher Ivan Illich and the economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen; however, it was during the 1970s that different voices brought attention to continuous acceleration, competition and the necessity of unlimited economic growth as the seeds of environmental and social conflicts3. As a response to this, degrowth advocates for the deceleration of economic growth, overproduction and overconsumption, and its replacement with solidarity, cooperation and care for the planetary ecological system, prioritising social and ecological well-being4. For the economist Serge Latouche, the slogan of degrowth «has an aim to strongly signal the abandonment of the target of growth for the sake of growth, a foolish objective whose engine is precisely the unrestrained search for profit by the holders of capital, and whose consequences are disastrous for the environment5 ». Therefore, to degrowth is necessary to get out of the productive demagogy, stepping out of the capitalist and consumerist society and breaking the paradigm of growth and development through a « societal » alternative.

Other positions from the South that open more relational ways to think about production and offer a societal alternative are those of the Buen Vivir6, which emerged from various Latin American communities and nations that developed a respectful interaction between nature and humans. In general terms, the idea of Buen Vivir considers a triune, with its first fundamental on 'identity', that is, living in harmony with oneself ; the second on 'equity', which refers to caring for a life in harmony with society; and finally, 'sustainability', which is living in harmony with nature7. Therefore, the Buen Vivir – a position that is not free of conflict due to its political and ontological implications when recognised and implemented – is a relevant voice against the controversial ideas associated with progress and development carried out in South America. However, unlike the Buen Vivir, the regional idea of growth and development promotes the continuous overexploitation of the land and colossal resource extraction projects for global production – as the continental infrastructure project IIRSA8 – that permanently undermines the interdependence between humans and non-humans and the well-living of these communities9.

Therefore, the Buen Vivir permits to illustrate the emergence of a plurality of perspectives with different aspirations and understandings from the communal, triggering particular forms of social organisations based on the recognition of the interdependence of lives and vulnerabilities, and a politics based on care and solidarity. Moreover, it contributes to recognise and value the existence of a pluriversal ontologic gaze, understood as « the transition from modernity's one-world ontology to a pluriverse of socionatural configuration10 », which is fundamental to nourish a transformation of the contemporary productive systems where design and the industry are largely involved. This requires acknowledging other relational forms for making and living besides economic determinism towards a more relational way of designing.

In this context, in which several positions call to reform the current logic of planetary production and consumption, there is a need for a significant reorientation of design further from a modern, one-world hegemonic western tradition dominated by functionalism, rationalism and industrialism, and closer to take responsibility and actions to build fairer production systems, considering social and environmental justice. Paradoxically, downsizing and re-contextualising the scope of production projects seem to be a reasonable margin of action in the face of the immeasurable scale of standardised devastation produced by predatory extractivism and industrialisation worldwide. Indeed, mid and low-scale production projects (being them manual or semi-industrial) outline more relational ways of designing and making that may re-orient with care the current modes of production and consumption in which industrial design is deeply interwoven; ways that can contribute to consider more plural, local and small scale designs.

1.2 Transitioning to relational designs with care

In design, different transition narratives account for the need for a significant transformation in our model of life and production and set their focus on imagining a design with an ethic of care towards our current reality and our future. For example, 'transition design' assumes our current socio-ecological crisis and unsustainable ways of living as the product of interlinked social and ecological stresses. To overcome this crisis, it is not possible to solve the stresses in isolation, but we need to start promoting a preventive change from design, which demands to take actions for transitioning to more sustainable futures and politically pursuing structural, long-term socio-cultural and ecological changes instead of focusing on problem-solving design orientations. In other words, transition designers should « acknowledge the extent of our social crises by advancing the practices of social and sustainable designing through the incorporation of multi-stage practice-oriented transformation11 ».

From a philosophical perspective raised on the global South, Tony Fry, followed by Arturo Escobar, envisages design as a potential discipline for caring and repairing. According to Fry, we can certainly recognise the disastrous impacts of the planetary socio-cultural and environmental crisis in the South, where 'defuturing practices' have created unsustainable conditions for the living12.

In this line, Escobar demonstrates how, when employed in developmental projects, design has contributed to creating defuturing worlds that have impoverished the possibilities to inhabit the earth in liveable conditions instead of pluralising and broadening them. Nevertheless, the author also suggests that if we can suppose that the contemporary world is a massive failure of design, maybe design has the means to draw possible exits from the crisis13.

These approaches summon the imperative need or a turn for 'sustainment' in design, understood as a process of long-term 'caring' and 'repairing' from now on. For Fry, Sustainment consists of repairing the broken worlds and reconstituting design for/by the South. Then, the design project for sustainment comprises the critical assessment of what exists in design together with local innovation and the definition of what is ontologically relevant for each community for building its future:

By implication, Sustainment (i) extends to every dimension of our species' environmental, economic, social, cultural and psychological existence, and (ii) exists as the counter direction to the ever-increasing condition of unsustainability as a force of extinction of all we are and the forms of life as we know it […] Finally, as a foundation of commonality, the Sustainment requires recognizing that our species' futural 'being-in-the-world' depends upon the acceptance of being-in-difference14.

Thus, as a futuring practice for caring and repairing, design for sustainment requires active engagement and skills to take a position based on the ability to respond in the face of present urgencies and future precarities15. It implies recognising and understanding the ontological differences and interdependencies between people and diverse forms of life beyond the dominant models, that is to say, a pluriversity of worlds or worlds within the world in which design can contribute to enabling the flourishing of life in the planet16.

Therefore, there is a need to broaden and pluralise accounts of the Anthropocene by summoning up scenarios strong enough to call for a politics of solidarity and an ethic of care based on recognising pluriversal modes of existences and our interdependencies among humans and with the ecosystems. Scenarios able to take intensive care of living territories or soils damaged by decades of severe and massive anthropized activities.

Accordingly, political scientists Berenice Fisher and Joan Tronto have widely contributed to model an ethic of care practicable to a large network of human and other-than-human lives. They suggest that care should be seen as « a generic activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, perpetuate, and repair our world so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web17 ». Indeed, the polysemantic word care implies interest (preoccupation, worry) and attention to others who are in need, while attention is accompanied by a gesture as part of an active process. Actually, for Tronto care is perhaps best thought of as a practice, a term which covers those two inseparable dimensions of care: thought (attention), and action (gesture).

Consequently, the ethic of care involves, according to the author, four inextricably linked moral elements identified as attentiveness (involves being attentive to the needs of others in order to respond to them), responsibility (supposes asking ourselves what we have done or not done, which has contributed to the appearance of the need for care, and which we must think about from now on), competence (amounts to « making certain that the caring work is done competently ») and responsiveness (suggests giving the means to the care receiver to respond or take part of the active care process)18. The adequacy of the care given in relation to the identified need is vital in an integrated practice of care.

For the disciplines of design, the taking care takes the shape of a gesture that involves a particular attention to the vulnerable, and places it at the core of its conceptualisation approach. Beyond the theory, this calls for a change of paradigm in design, a transition from a rational standardised mode of production and gestion towards a mode of relational production focused on the attention, able to reinforce the capacity of response of communities and individuals, and their autonomy of decision in the face of the present and future challenges19.

In this regard, and following Escobar's position20, a relational approach in design involves appreciating the network of relationships in which we interact, learn and live. Thus, we are all involved in spatial, territorial and identitarian connections that we must recognise to act responsibly and, therefore, take care of the other humans and other species with whom we constantly interact. Then we understand that relationality can attentively connect being, dwelling and making, and is opposed to homogenisation and individualism.

These re-orientations in design acknowledge the need for a transition with care when facing the current planetary crisis, and they recognise that there is not one standardized solution to face it, but instead, there are multiple, complex, and interconnected paths for a change. Moreover, these positions emphasise the importance of locality, the respect of 'difference', and the relevance of coping with conflicts and frictions, by being aware of our collective interdependencies and fragilities as the fundamentals to reform and reorient design and production as a relational process. As a consequence, the productive turn in design raises the question of scale in production and economies. Degrowing and Buen Vivir imply downscaling the production to territories, corresponding to their inhabitants' needs, resources, and know-how. In this regard, the long-time undervalued artisanal way of living, thinking and producing may inspire ways of downsizing the scale of productivity to gain interspecific resilience and interdependent sovereignties. This detour through craftsmanship is an attempt to draw new roads less travelled for design practices, between the inevitable global industrial market and autarchic local manual manufacturing.

2. Artisanship as a relational system of production

As part of a dominant Western narrative of industrialisation in which non-industrial design and production have often been marginalised21, some perspectives tend to promote design as a supportive discipline for crafts that contributes to adding value to the handmade objects, and encouraging the commodification of artisanal production.

These narratives have been particularly significant in the way they operate in South America, where the design projects were entangled with the ideas of modernity and industrialisation of the region. As stated by the designer Gui Bonsiepe, the history of industrial (and also graphic) design in Latin America dates back to the 1960s when design training programmes started to be created by ministries of technology, industries or cooperation and development centres connected to the processes of industrialisation and economic developmentalism22, as part of a strategy for the spreading of northern development programs that followed the Marshall Plan and claim for independence from colonies during the cold-war23. Nevertheless, already in the 1990s, Bonsiepe recognised that these attempts to integrate design in industrial production failed since the discipline remained a marginal activity, uprooted from significant production and framed mainly in the academic context rather than the industrial sphere24. To explain this situation, Bonsiepe made use of the theory of dependency and the conflicts between central and peripheral countries, a dynamic through which the Southern nations were dependent on the production and designs of the global metropolises25. Still, he acknowledged the limits of this theory that placed responsibilities on external factors; thus, he tried to find answers for the disciplinary problems of integration in the linguistic, discursive, economic, technical and representational limitations for design inside the Latin American nations.

Together with the frustrations expressed by Bonsiepe, it is essential to recognise that at different levels, the Southern countries have suffered severe deindustrialisation when facing the impossibility to compete with a liberalised market and the formation of global value chains26, therefore orienting their industrial production towards the extraction and exportation of raw materials, and to develop the service sector. Against this background of industrial decline, part of the field of professional industrial design turned to small scale production and towards collaborating with other oficios or crafts. While crafts or artesanías have been relevant in South America for being considered a means to improve social, cultural, and economic development, it was not until the first decade of the 2000s when the association between crafts and design was systematically encouraged through diverse projects27. These projects promoted the integration of design into crafts to achieve « cultural development » and design products that could transit between the local and the global with identity to encourage the growth of craft enterprises. Design for crafts was promoted to « introduce systematic harmony between demand, needs, production, innovation, consumption, waste, recycling, with a criteria of sustainable development and considering the preservations of heritages and identities28 ». While design for crafts became associated with profit, enterprise, economic growth and to support artisanal production, at some point and in an international level, it became perceived as an hegemonic mode to integrate the modern, productive and aesthetic values of design in the chains of traditional production29.

Considering this background and the discussion previously developed in the article, the following part examines how artisanal production, through its intrinsic interdependency with the future of ecosystems and communitarian governance, can support design practices grounded on other-than-industrial forms of production. For this, we shed lights on how crafts relationality can contribute to nourishing alternative ethic of care in design in the middle of predatory exploitation to consider more plural, local and small scale designs.

2.1 The diversity of crafts

The reality of artisanship or crafts is far from fitting within a unified consensual definition of a system or mode of production with agreed conventions. Instead, the ideas and practices associated with crafts are complex, heterogeneous, and as diverse as the context in which they take place, being interwoven with several ontological, cultural, economic and ecological dimensions.

Among the meanings associated with crafts, we find several characterizations that intend to give precision to the term by qualifying it through its origins and modes of transmission, such as the Popular Arts, Folk Arts, Indigenous or Traditional Crafts. Alternative denominations seek to define crafts through their artistic or functional orientation by locating these practices closer to art or design, or on how innovative artisans are when making use of means of production and technologies, as in 'Neo-Handicrafts', a specific branch of digital fabrication that among other streams, aims to promote the transforming potential of technology through its application to the typical handicraft manufacturing processes30. However, the polarisation of the position of crafts concerning the use of mechanised means of production and technological advance has raised historical criticism, since this antagonism between tradition and progress have contributed to reduce a very complex world of making into a set of dichotomies, like craft or industry, freedom or alienation, tacit knowledge or explicit knowledge, handmade or machine-made, among others31.

Other reductionist definitions often used by international institutions and policies tend to characterise artisanship based on the artisanal objects or products, as those pieces made with a predominant manual contribution and that use sustainable resources in the process of production32. However, alluding only to the artisanal product seems insufficient to address crafts interweaved practices, networks and heterogeneity. Due to this very diverse understanding of crafts, and as we will explore in the following section, our aim is far from establishing a singular definition and truncate this broad and rich pluriversity characterising artisanal production. Instead, we are interested in the relational expression of craft and its values to nourish reflections for transitioning to a design with care; consequently, we observe how an ontology of crafts founded on values like the appreciation of identity, equity, and sustainability, might guide us towards more relational modes to think about design and production.

2.2 Revisiting relational values in crafts for a transition in production

Due to the variety of crafts, it is illusory to consider one singular craft as 'the' specific, radical and unequivocal alternative to reverse or replace the prevailing capitalist system of industrial overproduction and consumption, and it is necessary to recognise that craftsmanship is also involved in that logic of making and commercialising. Thus, instead of romanticising artisanal production and avoiding the inadequacy or normative interpretation of crafts in its general use33, we focus on the artisans' relational process as a possible ethical and political approach to reflect on the transitioning of design and production. To do so, we develop hereinbelow case studies held by the two authors with craft communities in Chile and Guatemala, that address the issue of relationality by exploring the artisanal mode of production in these communities that merge living and making in a relationship of interdependence and care between the members, and with their environment.

On the first hand, we present the investigation conducted between 2017 and 2020 as part of one of the author's doctoral thesis, which focuses on following the controversies and frictions between tradition and innovation in Chilean artisanal production34. This research that involves relevant actors and crafts communities in Chile permitted to carry out more than 50 interviews among artisans and people linked to crafts, mainly from the village of Pomaire, where more than 230 families work in pottery production and its commercialisation, and where the production moved from traditional pieces and process to more utilitarian objects fabricated in large scales and distributed local circuits of commercialisation. In parallel, interviews were carried out with relevant actors from the craft sector, for example, members and spokespersons of Difusión-Artesanía35, an autonomous and independent group of Chilean artisans driven by a genuine concern for the well-being of all their peers, that search and share relevant information to connect, orient and empower artisans; and with other authorities that work on the promotion of handicrafts in Chile, for example, members of the Fundación Artesanías de Chile36.

Figure 1. Map of Pomaire. The village is located close to Melipilla, between the capital city of Santiago de Chile and the international port of San Antonio.

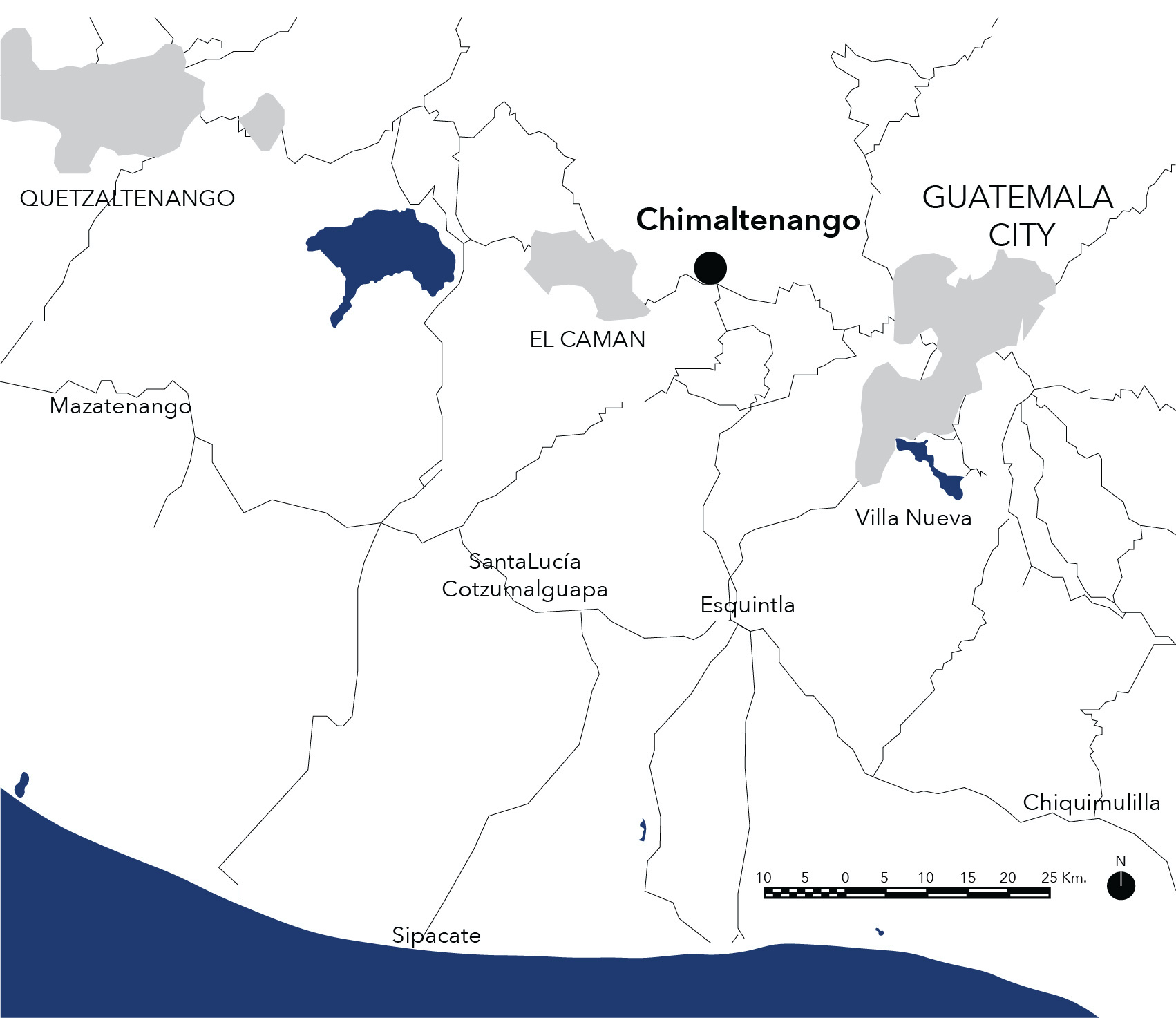

On the other hand, a design-based investigation led by the second author between 2017 and 2020 look into growing vulnerabilities observed in the Global South craft sectors (even in business models based on social and solidarity values, such as Fair Trade) due to their extreme dependency on distant markets37. It examines the case of women weavers from the Guatemaltecan cooperative Aj Quen located in Chimaltenango, Guatemala, which was founded in 1989, when Fair Trade represented an economic alternative towards development through the access to the international market38. Its core business is the production of local textile handicrafts commercialised through long-standing fair and international solidarity trade partnerships with many members of the European Fair Trade Association (EFTA). While in 2017, 80% of Aj Quen's revenue still came from the international Fair Trade market, the craft orders from the European Fair Trade sector strongly declined in recent years. Therefore, as the dependency on the external market interferes in the autonomy of this craft community, the viability of this economic model is called into question. In this context, the co-design research aimed to find joint solutions starting from their local environment and their craft values.

Figure 2. Map of Chimaltenango, located in the south-west region of Guatemala where the cooperative Aj Quen is operating, 54km from the capital city of Guatemala.

In 2020, the global pandemic unsurprisingly exacerbated the scenario previously described for many actors of the craft sector. Confronted with the decline in exportation and the massive reduction of tourism flows, artisans faced a singular and unprecedented way of isolation and precarity39. A virtual meeting organized in May 2020 together with designer Kevin Murray40 got together artisans from Asia, Africa and Latin America (among them a representative of Aj Quen) to discuss craft alternatives of « Life after lockdown ». The gathering shed light on the vulnerabilities of artisanal production when inserted in the global system of mass planetary production and consumption, rendering visible an opportunity to raise awareness among the producers and consumers on how important is each actor involved in the craft value chain, and how interdependent are their processes, between them, with nature and other sectors of society41.

The case studies discussed reveal common values intrinsically linked to a strong expression of relationality in crafts. A relationality understood as a way of being in the world engaged with the collective; a mode of production in which the significance of making consists of interdependent relations between society, environment, and living species. Besides, the relationality of crafts copes with conflicts and contributes to articulating new possibilities, alternatives, and resistances constructed through this very difference, the territory, and a politics of responsibility. Therefore, the relational approach in artisanship developed in the following sections appears to be a possible way to face the current heterogeneous socio-ecological crisis.

2.2.1 Living and making within a web of life

We find that several of the artisans interviewed in Pomaire stated that artisanal production tended to be regarded within a system of values focused on the product, not on the producers or the environment. However, they expressed that they considered themselves a part of the relation between the subject, the material, the environment and the society, not only the producers of an artisanal object. This relationship is also evident in the Guatemaltecan case, where women craft weaver share their time between the family farming activities and the community craft work based on Fair Trade principles. Those are founded on the recognition and promotion of the role of the community and its environment in the craft value chain. They are aware that they inherited their skills from their ancestors and territories for generations. It is also striking how the designs change with the transformation of their environment (we can observe on their traditional huipiles new patterns influenced by occidental figures and celebrations, for instance).

Beyond definitions that focus on specialised manual production, the sociologist Richard Sennett extends the concept of craftsmanship to define it as a shared ethos based on a compromise to perform well a task42. Moreover, as we could trace, crafts correspond to a form of being, dwelling and making shared among artisans, who conceive their work as a form of life or a life project based on social responsibility, which requires attentiveness to the otherness, and to the need for caring the environment, two fundamental aspects to drive a production process able to « care about », and « take care of », following the ethic of care. Actually, we can find the moral criteria developed by Tronto and Fishers in the testimonials of many artisans who expressed having chosen their craft for the contribution and value of their trade when creating, transforming and materialising something useful to the society. This appreciation is conducive to understand the relationality presented in the craftsmanship as committed with a social responsibility for making.

This responsibility is expressed by one of the spokesperson of the group Difusión-Artesanía when discussing about his choice of being an artisan and the complexities of this life project. The artisan Sergio Pallaleo, of Mapuche origin, emphasises that for him, being an artisan is a communitarian engagement which is not only guided for the aim of making, but is a strong message of resistance to the capitalist system of production, a way of living in coherence with his culture and the environment43.

Furthermore, this position exemplifies how the artisan defines making as a social commitment and a political action for resistance to the global, mass production and to the lack of government policies to support artisans in the Chilean context44. In this statement, we can infer that the artisan's attention is in his social engagement with resistance, while a gesture accompanies this attention, that is, the commitment to the artisanal practice as a life project. Thus, his position covers those two inseparable dimensions of care : thought as an attention and action as a gesture.

2.2.2 Building autonomy within interdependence

As a pre-industrial activity based on the autonomy of production, craftsmanship has the advantage of functioning through a fast iteration between the maker and the object, shaping a highly resilient and resistant system when operating through the small-scale production techniques45.

In Pomaire, the artisans define autonomy as knowing and controlling their means of production without technological dependence, achieving self-sufficiency or community-sufficiency. Therefore, the tools and resources that require external control from outer supply chains – like implementing gas kilns that require gas loads supplied by enterprises located elsewhere – are refused by the artisans. Instead, they prefer to control the accessibility to fuels that they obtain without constraints, like the preference for using lampazo or slab wood, easily collected in the village.

Thus artisanship is intrinsically founded on this principle of freedom, on knowing how to use manufacturing tools autonomously. 'Knowing how' to use tools not only implies using them for productive activities but also refers to the capability of the artisan or someone belonging to the community to repair the tools and modify them considering the intentions of the craftsmen and the characteristics of the materials.

Figure 3. The use of wood-fired kilns prevails in Pomaire, despite various initiatives to replace them with gas kilns. The artisans favour their autonomy to acquire and manage the fuel.

The case of the women weavers from Guatemala is quite different from the one of Pomaire but serves to interrogate the notion of autonomy as a fundamental value of relationality, enabling artisans to be sovereign in governance and united in resilience.

Indeed, the analyses of the flows, resources and players involved in the craft value chain revealed knots of non-reciprocal dependencies hard to untangle. Both the acquisition of raw materials and the marketing and sales of handicrafts depend on external players. The cotton is imported from Asia46, and dyed in Guatemala. It is nearly impossible to track the environmental and social conditions of production of the imported cotton. While the international market for Fair Trade handicrafts is slumping, there is a negotiation for lower prices, as stated by the manager of Aj Quen, José Victor Pop Bol : « customers are demanding even cheaper prices. Before, that didn't worry us, as we were receiving subsidies from international cooperation which allowed us to cover our running costs, even if our trade balance was in the red. We were doing it so the craftswomen could still have work47 ».

Between 1989 and 1994 handicraft orders provided work for 40 groups of organised producers. The number of groups benefiting from Fair Trade fell to 26 from 1995 onwards. There are 16 today. The main factors for this reduction are the mismatch between the product and the European consumer's taste and the high cost of handicraft compared to industrial copies of the product (mainly coming from China). In their account, many craftswomen explain that in order to work, they often accept small orders negotiated directly with the customer, who has no hesitation in paying them half the fair price established with Aj Quen48. This shows how vital it is to win back autonomy for productive communities whose living conditions depend on non-reciprocal relationships.

Supporters of a post-development and pluriversal approach advocate an economic model of resilience rather than efficiency, which consists of fostering production and consumption diversity, and encouraging the autonomy of governance at the local level to reduce dependence on global production and distribution channels, with a territorial approach that promotes local economies to benefits the environment. In that perspective, in 2018, the Chilean craft Fair Trade cooperative Pueblos del Sur49 – also a historical partner of the European Fair Trade Organisations members – , committed to developing the Fair Trade market at the local and national level. Reterritorialising the value chain regionally to strengthen autonomy is part of the design-led project held with the craftwomen from Aj Quen.

Besides, being grouped in a cooperative or community allows the craft workers to produce and negotiate collectively for decent work conditions and fair remuneration, and thus to conquer some autonomy. Despite the huge challenges faced by the Guatemaltecan community, their being associated represents a strength in the face of the transition needed for their business.

Autonomy in crafts also implies building greater co-responsibility between every economic player on the value chain, at the legal, economic, social and environmental levels. It is, consequently, intrinsically connected to the first value of relationality developed above.

According to the philosopher Ivan Illich, whose works focused on the critiques of industrial society and on the value of autonomy « a convivial society should be designed to allow all its members the most autonomous action by means of tools least controlled by others. People feel joy, as opposed to mere pleasure, to the extent that their activities are creative; while the growth of tools beyond a certain point increases regimentation, dependence, exploitation, and impotence50 ». In this line, the artisans from the village of Pomaire emphasise the value of autonomy as the possibility of freely managing their tools and activities according to their needs and wills, to practice their knowledge in coherence with their life projects, and allowing them to achieve production in harmony with their lives.

However, and almost as a contradiction to the principle of autonomy, the artisans continuously recognise their dependence on materiality, environment, and on other artisans from the community. For example, the artisanal pieces from Pomaire are often produced through several distributed interactions between different artisans, who contribute through their particular knowledge and expertise in the shaping of an object. This form of production shows the third party organisation in the pottery making chain based on the specificity of labour, in which many tasks of the clay processing cycle are interconnected.

Thus, autonomy should not be understood in a modern individualist project, but as the attention to, and recognition of the otherness, following an ethic of care51, and as a moral criteria of responsiveness that gives the means to each individual and community to take an active role in the relationship with others (humans and non-humans) on the value chain.

Autonomy, in that way, means a collective project of interdependent sovereignties where people and communities organise themselves around an economical core, as the clay for pottery making, in which people can autonomously organise their production to define and decide their life projects according to their expectations and competences. The relationship of belonging to and of interdependence with a community appears as one of the principal strengths of crafts – both in politics and economics – for developing greater resilience when facing current and future crises.

2.2.3 Crafts reterritorialisation as key collective resilience

As Vandana Shiva expressed, « parallel to the destruction of nature as something sacred was the process of the destruction of nature as commons52 ». Revisiting this affirmation, we can see that several craft communities have been affected by the global logic of deterritorialisation and predatory extractivism that impact the traditional and common natural sources of materials used by many artisans. In this regard, many women weavers from indigenous and afro-descendant communities in Chile manifested the tensions they have to face with the mining, forestry and salmon farming industries settled in their territories, which directly affect the collection of the raw materials they use for their textiles53, having strong implications in their chains of production. Therefore, by following the artisans and their interactions with materials presented in the case studies, we could identify the impact of the ecological crisis that led to the displacement of traditional areas of material supply for production due to their privatisation, change of the use of the soil, or the massive exploitation that directed to a depletion of natural resources. Even when artisans also need to extract materials for their production, this type of extraction tends to be marginal compared to the deterioration of ecosystems produced by extractive enterprises.

Figure 4. Sequence of images of two artisans from Pomaire searching and extracting materials from a clay pit. The craftsmen recognise the location of the clay source based on their previous experiences on the territory. When they identify the clay pit, they initiate the negotiation with the private lands owners to start extracting material.

This phenomenon appears in the current search of artisans for new sites for material supply far from the village of Pomaire due to the loss of the traditional common places for extraction. The extraction sites around the village have turned inaccessible, reserved for agriculture or urban infrastructure, so the artisans need to search for new clay pits in the surrounding areas permanently, where they pay to extract the material. Another example of material conflict is in the pottery community of Quinchamalí and Santa Cruz de Cuca, in Chile, where accessible spaces for clay extraction are being blocked and planted with monocultures of pine and eucalyptus, threatening the traditional pottery-making of the area. This menace led to the search for protection of the resources through a nomination for safeguarding the immaterial cultural heritage presented to Unesco, to generate an action against the cultural and ecological impact of monocultures in the area54.

Figure 5. Map of the extraction sites for pottery production in Pomaire. Nowadays, the clay is no longer extracted in the village of Pomaire but collected between Pomaire and the coastal regions of San Antonio and Valparaíso. The wood for the kilns is obtained between 100 km north and 150 km south of the village.

The case studies in this article contribute to highlight how the constant search for materials provides insights into the resilience of the crafts' production chains and practices, the conception of objects, and the know-how for making. As artisanal production in Pomaire operates on a low scale, it is possible to introduce minor modifications or adaptations in the material flows and the different manufacturing processes to include materials collected beyond the traditional sources. This process involves a technical and mechanical organisation of the extraction and distribution of the clay and, at the same time, a collective and empiric knowledge that allows the artisans to work with the material's distinctive characteristics. The artisans adjust the mixtures of various soils to find the necessary balance for modelling the pieces, adapting their shapes and composition to produce appropriate objects corresponding to the material variability. However, the reterritorialisation often implies controversies, frictions and resistance of the craft communities, and even their mobilisation to protect the collective resources, as in the community of Quinchamalí55.

While these conflicts over territories permit us to understand a displacement and deterritorialisation in an acute sense that considers the fragilities and modern/colonial logics that lie in the territory, they also allow visualising the origin of a territorial reconstruction through a caring reterritorialisation56. This restoration appears on the resilience of crafts communities due to their relational knowledge about the territories and the materials that permits them to search for new places for the common use of resources. These processes of displacement can be observed from the negative sense of fragility and territorial precariousness, or in opposition, these processes can contribute to shedding light on the potential of new places to sustain craft and cultural production despite the increased commodification of the land, or as relational spaces, that call for recognising with responsibility the importance of humans and non-humans in their connections between identity and environment.

Thus, faced with deterritorialised globalisation, the re-territorialisation of part of the productive systems suggests a re-territorialisation of flows and responsibilities for social, environmental and cultural damages. A context in which artisans and designers – as creators, producers and political actors – play essential roles. For example, in Colombia, the post-conflict also implies building peace with ecosystems damaged by widespread monocultures. Since 2014, a project led by Colombian industrial designers from the Tadeo Lozano University of Bogotá, together with the governmental organisation Agrosavia, and fique craft communities from the regions of Boyacá and Nariño, opened new perspectives of collaboration between the craft and industry sectors, taking into consideration the relations that tie production with a territory, its ecosystems and inhabitants. Fique (furcraea spp, a type of Agave native widely cultivated in Colombia and Ecuador), is the only natural fibre in Colombia that combines both manual and industrial processes to fabricate a large diversity of product from baskets to shoes. More than 70.000 families’ livelihood around the country depends on the fique value chain, strongly challenged by the apparition of plastic in the ’70s and ’80s. In this context, the social design investigation analysed the artisanal cultivation and transformation processes of fique, its difficulties and potentialities along the value chain to optimise every part of the plant, from the crop to the design of craft products. A significant outcome was designing a semi-automatic system to separate fibres, juice, and bagasse of fique leaves. However, the strategy for transferring the fique separation system to rural areas depended on the particular characteristics of the local communities and the regions where the system was and will be implemented. The project results emerged in 2019, simultaneously with the declaration of Boyacá as a department « free from plastic ». This political action contributes to revitalising the economy and development vegetal fibres, mainly the fique fibre that has always been widely produced in Colombia57.

Conclusion

The anthropogenic standardisation and massification of governance, production and consumption in response to goals of progress and efficiency have been as disastrous as they have been effective in shaping a new era characterised by an alarming weakening of the conditions of life on earth for all species. Local and national economies became, for better or for worse, increasingly dependent on distant markets and international channels, including areas as essential to life as food and health, or even sectors based on solidarity and Fair Trade.

In this precarious post-industrial context, a major challenge in the sphere of production consists of repairing the living territories and the ecosystems and social ties that sustain them. It comprises weaving or strengthening a network of plural economic and productive models, narratives and players, sovereign in governance and united in resilience.

Consequently, this article defends that design must be reoriented towards caring values sustained by recognising humans’ interdependence with other species in life and death. Thus, a design practice can be defined as « caring » when it pursues the goal of perpetuating or repairing the conditions of life in our world, which has become particularly vulnerable. Whether in relation to governance or the productive system, an ethic of care involves avoiding any reflex to standardise responses to the impending social and environmental problems.

Considering craft as a design practice (being it manual or semi-industrial), especially in the Latin American context where the industrialisation project has failed, it is worth analysing its strength and singularity in the conception and productive systems. Without romanticising, the article delves into the intrinsically « relational » mode of thinking, doing and living in the craft sector (namely in a relationship of interdependence and care between the members of a community and with the environment), as an effort to draw avenues for transitioning from a rational standardised mode of design and production, towards a relational one. This relational design takes care of the growing vulnerabilities and can reinforce the capacity of response and autonomy of communities and individuals in the face of the present and future challenges.

In this regard, the two case studies from the Global South presented in the second part of the article are helpful to observe that despite the conflicts faced by the artisans – like the tensions for reaching raw materials in the case of Pomaire or the need for less dependent structures in the case of Guatemala –, they sustain a form of being and making that has contributed to generate resistance or resilience to mass and globalised production. Through their engagement in networks formed from their identity, territorial roots, common interests, and the recognition of their interdependence, artisans seem to share a relational way of life sustained by responsibility, autonomy and reterritorialisation as a continuous adaptation when facing conflicts and difficulties, establishing a resilience that favours and needs sustainable practices for being and making in the world.

Consequently, the article highlights a close link between relationality and reterritorialisation that is necessary to consider for future design and production programs ruled by an ethic of care. Pluralizing, downsizing and re-contextualising the scope of production projects seem to be a credible margin of action in the face of the immeasurable scale of standardised devastation produced by predatory extractivism and industrialisation worldwide.

Bibliography

• Adamson, Glenn, The Invention of Craft, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

• Bonsiepe, Gui, El diseño de la periferia : debates y experiencias, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1985.

• Bonsiepe, Gui, « Perspectivas del Diseño Industrial y Gráfico en América Latina », in Temes de Disseny, vol. 4, 1990.

• Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes (CNCA), « Proceso de participación ciudadana para la construcción de la política de fomento al diseño 2017-2022 ; documento de apoyo a la participación : principales problemáticas del sector », CNCA, Santiago, 2017.

• Correa, Felipe, Beyond the City: Resource Extraction Urbanism in South America, Austin, University of Texas Press, 2016.

• Craft Revival Trust, Artesanías de Colombia, Unesco, Designers Meet Artisans: A Practical Guide, New Dheli, 2005.

• Escobar, Arturo, Autonomía y diseño : La realización de lo comunal, Popayán, Universidad del Cauca - Sello Editorial, 2016.

• Escobar, Arturo, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds, London, Duke University Press, 2018.

• Escobar, Arturo, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1995.

• Escobar, Arturo, « Response: Design for/by [and from] the “The Global South” », in Design Philosophy Papers, vol. 15, n°1, 2017 [online] https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2017.1301016

• Fleury-Perkins, Cynthia and Fenoglio, Antoine « Le design peut-il aider à mieux soigner? le concept de proof of care », in Soins : Philosophie à l’hôpital, n°834, Paris, April, 2019 [online] https://chaire-philo.fr/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Soin\_1513-Fleury\_ok.pdf

• Fry, Tony, « Design for/by “The Global South” », in Design Philosophy Papers, vol. 15, n°1, 2017 [online] https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2017.1303242

• Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1971.

• Gimeno Martínez, Javier and Floré, Fredie (eds.), Design and Craft: a History of Convergences and Divergences, 7th Conference of the International Committee of Design History and Design Studies, Vlaamse Koninklijke Academie van België voor Wetenschappen en Kunsten, Brussels, September, 2010.

• Gómez Pozo, Carmen, « La gestión de Diseño entre la innovación y la tradición », in Revista de Cultura y Desarrollo : Dinámica de la artesanía latinoamericana como factor de desarrollo económico, social y cultural, Part 5, vol. 6, Havana, Unesco, 2009.

• González Arnao, Walter, Neo-Handicrafts in America: Methods to Incorporate Digital Fabrication Processes into Handicrafts, Lima, Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería, 2019.

• Haesbaert, Rogério, « Del Mito de La Desterritorialización a La Multiterritorialidad », in Cultura y Representaciones Sociales, vol. 8, n°15, 2013, pp. 9-42.

• Halvorsen, Sam, « Decolonising Territory: Dialogues with Latin American Knowledges and Grassroots Strategies », in Progress in Human Geography, vol. 43, n°5, 2019 [online] https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518777623

• Haraway, Donna, Staying with the trouble. Making kin in the Chthulucene, Durham, Duke University Press, 2016.

• Hidalgo-Capitán, Antonio and Cubillo-Guevara, Ana, « Deconstruction and Genealogy of Latin American Good Living (Buen Vivir). The (Triune) Good Living and Its Diverse Intellectual Wellsprings », in International Development Policy, n°9, 2019 [online] https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.2351

• Illich, Ivan, Tools for Conviviality, New York, Harper & Row, 1973.

• International Trade Centre Unctad/WTO, International Symposium on Crafts and the International Market: Trade and Customs Codification; Final Report, Manila, Unesco, 6-8 October 1997 [online] https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000111488

• Larrère, Catherine, « La nature a-t-elle un genre ? Variétés d'écoféminisme », in Cahiers du Genre, vol. 59, n°2, 2015, pp. 103-125 [online] https://www.cairn.info/revue-cahiers-du-genre-2015-2-page-103.htm

• Latouche, Serge, « Degrowth », in Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 8, n°6, 2010 [online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.02.003

• Lees-Maffei, Grace, and Sandino, Linda, « Dangerous Liaisons: Relationships between Design, Craft and Art », in Journal of Design History, vol. 17, n°3, 2004.

• Meadows, Donella H., et al., Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind, New York, Universe Books, 1972.

• Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio, Gobierno de Chile, Voces Creadoras : Diálogos Entre Cultoras Indígenas y Afrodescendientes, Asát'ap 2016-2017, Santiago, Ministerio de las Culturas, 2018.

• Moore, Jason W., Capitalism in the Web of Life; Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital, London, Verso, 2015.

• Salgado Cofré, Daniela, « La Vuelta a La Producción Global y La Alternativa Relacional de Los Artesanos », in Revista Acto & Forma, vol. 5, n°9, 2020, p. 17-21 [online] http://actoyforma.cl/index.php/ayf/article/view/106/91

• Salgado Cofré, Daniela, Contemporary Frictions in Traditional Artesanías: Transformations and Controversies in the Making of Pomaire's Pottery Production [unpublished doctoral thesis], Université libre de Bruxelles, 2021.

• Schindler, Seth, et al., « Deindustrialization in cities of the Global South », in Area Development and Policy, vol. 5, n°3, 2020. DOI: 10.1080/23792949.2020.1725393

• Shiva, Vandana, « Resources », in Sachs, Wolfgang, The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 1999.

• Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2008.

• Tonkinwise, Cameron, « Design for Transitions - From and To What ? », in Critical Futures Symposium, Articles n°5, 2015 [online] https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/critical\_futures\_symposium\_articles/5

• Tronto, Joan C., Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care, London, Routledge, 1993.

• Vallejos Fabres, Cristóbal, « Presencia, olvido e insistencia. Comentario sobre la relación entre diseño y desarrollismo en Chile », in RChD: creación y pensamiento, vol. 1, n°1, 2016 [online] doi:10.5354/0719-837X.2016.44316

• Vanwambeke, Estelle, Crafts, development policies and Fair Trade: Challenges and perspectives through the lens of design, Bierges, Oxfam, December 2017.

• Vanwambeke, Estelle, Stories of “The World After”: bringing care into economic and political relations. A relational approach through crafts, Oxfam, 2020.

• Vyas, H. Kumar, « The Designer and the Socio-Technology of Small Production », in Journal of Design History, vol. 4, n°3, 1991, pp. 187-210 [online] https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/4.3.187

Websites

• [online] https://www.degrowth.info/en/what-is-degrowth/ (visited on July 9th 2020).

• [online] https://garlandmag.com/ (visited on March 23rd 2020).

• [online] https://www.facebook.com/Pueblos-del-Sur-Chile-COMERCIO-JUSTO-FAIR-TRADE-211318778908708/ (visited on April 12th 2020).

• [online] https://www.24horas.cl/regiones/nuble/alfareras--quinchamali-santa-cruz-de-cuca--patrimonio-de-la-humanidad-unesco-4700495 (visited on March 26th 2021).

Rights and captions

• Figure 1. Map of Pomaire. The village is close to Melipilla, between the capital city of Santiago de Chile and the international port of San Antonio.

© Daniela Salgado Cofré.

• Figure 2. Map of Chimaltenango, located in the south-west region of Guatemala where the cooperative Aj Quen is operating, 54km from the capital city of Guatemala.

© Daniela Salgado Cofré.

• Figure 3. The use of wood-fired kilns prevails in Pomaire, despite various initiatives to replace them with gas kilns. The artisans favour their autonomy to acquire and manage the fuel.

© Daniela Salgado Cofré.

• Figure 4. Sequence of images of two artisans from Pomaire searching and extracting materials from a clay pit. The craftsmen recognise the location of the clay source based on their previous experiences on the territory. When they identify the clay pit, they initiate the negotiation with the private lands owners to start extracting material.

© Daniela Salgado Cofré.

• Figure 5. Map of the extraction sites for pottery production in Pomaire. Nowadays, the clay is no longer extracted in the village of Pomaire but collected between Pomaire and the coastal regions of San Antonio and Valparaíso. The wood for the kilns is obtained between 100 km north and 150 km south of the village.

© Daniela Salgado Cofré.

-

See: Tronto, Joan C., Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care, London, Routledge, 1993, pp. 156-157 and Larrère, Catherine, « La nature a-t-elle un genre ? Variétés d'écoféminisme », in Cahiers du Genre, vol. 59, n°2, 2015, pp. 103-125 [online] https://www.cairn.info/revue-cahiers-du-genre-2015-2-page-103.htm ↩

-

Moore, Jason W., Capitalism in the Web of Life; Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital, London, Verso, 2015. ↩

-

See: Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1971 and Meadows, Donella H., et al., Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind, New York, Universe Books, 1972. ↩

-

[online] https://www.degrowth.info/en/what-is-degrowth/ (visited on July 9th 2020). ↩

-

Latouche, Serge, « Degrowth », in Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 8, n°6, 2010, p. 519 [online] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.02.003 ↩

-

The Buen Vivir is not a homogeneous approach but arises from the shared ontologies and values that each particular community assigns to it. Thus, these groups configure their sustainable practices, social and material interactions for the well-being, which have been included on official paths to acknowledge common aims, such as the Buen Vivir integration into the constitutional texts of Ecuador (2008) and Bolivia (2009). ↩

-

Hidalgo-Capitán, Antonio and Cubillo-Guevara, Ana, « Deconstruction and Genealogy of Latin American Good Living (Buen Vivir). The (Triune) Good Living and Its Diverse Intellectual Wellsprings », in International Development Policy, n°9, 2019, pp. 23-50 [online] https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.2351 ↩

-

See more about the impact of IIRSA and other projects in Correa, Felipe, Beyond the City: Resource Extraction Urbanism in South America, Austin, University of Texas Press, 2016. ↩

-

Halvorsen, Sam, « Decolonising Territory: Dialogues with Latin American Knowledges and Grassroots Strategies », in Progress in Human Geography, vol. 43, n°5, 2019, pp. 790-814 [online] https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518777623 ↩

-

Escobar, Arturo, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds, London, Duke University Press, 2018, p. 4. ↩

-

Tonkinwise, Cameron, « Design for Transitions - From and To What ? », in Critical Futures Symposium, Articles n°5, 2015 [online] https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/critical\_futures\_symposium\_articles/5 ↩

-

Fry, Tony, « Design for/by “The Global South” », in Design Philosophy Papers, vol. 15, n°1, 2017, p. 4 [online] https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2017.1303242 ↩

-

Escobar, Arturo, Autonomía y diseño : La realización de lo comunal, Popayán, Universidad del Cauca - Sello Editorial, 2016, pp. 49, 51. ↩

-

Fry, Tony, « Design for/by “The Global South” », op. cit., pp. 15-16. ↩

-

Haraway, Donna, Staying with the trouble. Making kin in the Chthulucene, Durham, Duke University Press, 2016. ↩

-

Escobar, Arturo, « Response: Design for/by [and from] the “The Global South” », in Design Philosophy Papers, vol. 15, n°1, 2017, pp. 39–49 [online] https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2017.1301016 ↩

-

Tronto, Joan C., Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care, op. cit., p. 103. ↩

-

Ibid., pp. 127-135. ↩

-

Fleury-Perkins, Cynthia and Fenoglio, Antoine « Le design peut-il aider à mieux soigner? le concept de proof of care », in Soins : Philosophie à l’hôpital, n°834, Paris, April, 2019 [online] https://chaire-philo.fr/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Soin\_1513-Fleury\_ok.pdf ↩

-

Escobar, Arturo, « Response: Design for/by [and from] the “The Global South” », op. cit., pp. 39-49. ↩

-

See: Gimeno Martínez, Javier and Floré, Fredie (eds.), Design and Craft: a History of Convergences and Divergences, 7th Conference of the International Committee of Design History and Design Studies, Vlaamse Koninklijke Academie van België voor Wetenschappen en Kunsten, Brussels, September, 2010. ↩

-

For an example of the influence of economic developmentalism in South America and the attempts to encourage the processes of industrialisation of the region through design practices integrated in Chile, see: Vallejos Fabres, Cristóbal, « Presencia, olvido e insistencia. Comentario sobre la relación entre diseño y desarrollismo en Chile », in RChD: creación y pensamiento, vol. 1, n°1, 2016, pp. 105-111 [online] doi:10.5354/0719-837X.2016.44316 ↩

-

See: Escobar, Arturo, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1995. ↩

-

Bonsiepe, Gui, « Perspectivas del Diseño Industrial y Gráfico en América Latina », in Temes de Disseny, vol. 4, 1990, pp. 131-134. ↩

-

Bonsiepe, Gui, El diseño de la periferia : debates y experiencias, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1985. ↩

-

See : Schindler, Seth, et al., « Deindustrialization in cities of the Global South », in Area Development and Policy, vol. 5, n°3, 2020, pp. 283-304. DOI: 10.1080/23792949.2020.1725393 ↩

-

See: Craft Revival Trust, Artesanías de Colombia, Unesco, Designers Meet Artisans: A Practical Guide, New Dheli, 2005. ↩

-

Gómez Pozo, Carmen, « La gestión de Diseño entre la innovación y la tradición », in Revista de Cultura y Desarrollo : Dinámica de la artesanía latinoamericana como factor de desarrollo económico, social y cultural, Part 5, vol. 6, Havana, Unesco, 2009, pp. 3-18. ↩

-

Part of the discussion developed at the International Seminar of Public Policies for the Artisanal Sector, organised in Chile, 2015. See the report: Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes (CNCA), « Proceso de participación ciudadana para la construcción de la política de fomento al diseño 2017-2022 ; documento de apoyo a la participación : principales problemáticas del sector », CNCA, Santiago, 2017, pp. 3-4. ↩

-

González Arnao, Walter, Neo-Handicrafts in America: Methods to Incorporate Digital Fabrication Processes into Handicrafts, Lima, Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería, 2019, p. 11. ↩

-

Adamson, Glenn, The Invention of Craft, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, p. xii. ↩

-

International Trade Centre Unctad/WTO, International Symposium on Crafts and the International Market: Trade and Customs Codification; Final Report, Manila, Unesco, 6-8 October 1997, p. 6 [online] https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000111488 ↩

-

Lees-Maffei, Grace, and Sandino, Linda, « Dangerous Liaisons: Relationships between Design, Craft and Art », in Journal of Design History, vol. 17, n°3, 2004, pp. 207-219. ↩

-

Salgado Cofré, Daniela, Contemporary Frictions in Traditional Artesanías: Transformations and Controversies in the Making of Pomaire's Pottery Production [unpublished doctoral thesis], Université libre de Bruxelles, 2021. ↩

-

Crafts-Diffusion Group. ↩

-

Chilean Crafts Foundation. ↩

-

Vanwambeke, Estelle, Crafts, development policies and Fair Trade: Challenges and perspectives through the lens of design, Bierges, Oxfam, December 2017. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Vanwambeke, Estelle, Stories of “The World After”: bringing care into economic and political relations. A relational approach through crafts, Oxfam, 2020. ↩

-

Kevin Murray is designer, coordinator of the community of artisans Garland and Senior Vice President of the World Crafts Council in the Asia Pacific region. See: [online] https://garlandmag.com/ (visited on March 23rd 2020). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2008, p. 21. ↩

-

Salgado Cofré, Daniela, Interview with Sergio Pallaleo, from the group Difusión Artesanía, Santiago, December 4th 2019. ↩

-

Salgado Cofré, Daniela, « La Vuelta a La Producción Global y La Alternativa Relacional de Los Artesanos », Revista Acto & Forma, vol. 5, n°9, 2020, p. 20. ↩

-

Vyas, H. Kumar, « The Designer and the Socio-Technology of Small Production », in Journal of Design History, vol. 4, n°3, 1991, pp. 187-210 [online] https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/4.3.187 ↩

-

National production of cotton began to decrease from the end of the 19th century (at which time industrially spun North-American cotton appeared on the market), to be totally replaced these days by the importation of Asian cotton. ↩

-

Vanwambeke, Estelle, Crafts, development policies and Fair Trade: Challenges and perspectives through the lens of design, op. cit., pp. 33-34. ↩

-

This case of extreme dependence on the international market is far from being isolated, as in Kenya, for example, where there is no local consumer market for the crafts of the region even if historically these craft products were made and used locally, which leave artisans in a dependent condition. This reality has been related by a Kenynan craft organisation member of the Garland Community, during the « Life after lockdown meeting ». See: Vanwambeke, Estelle, Stories of “The World After”: bringing care into economic and political relations. A relational approach through crafts, op. cit. ↩

-

See: [online] https://www.facebook.com/Pueblos-del-Sur-Chile-COMERCIO-JUSTO-FAIR-TRADE-211318778908708/ (visited on April 12th 2020). ↩

-

Illich, Ivan, Tools for Conviviality, New York, Harper & Row, 1973, pp. 20-21. ↩

-

Tronto, Joan C., Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care, op. cit. ↩

-

Shiva, Vandana, « Resources », in Sachs, Wolfgang, The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 1999, p. 210. ↩

-

Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio, Gobierno de Chile, Voces Creadoras : Diálogos Entre Cultoras Indígenas y Afrodescendientes, Asát'ap 2016-2017, Santiago, Ministerio de las Culturas, 2018, p. 51. ↩

-

[online] https://www.24horas.cl/regiones/nuble/alfareras--quinchamali-santa-cruz-de-cuca--patrimonio-de-la-humanidad-unesco-4700495 (visited on March 26th 2021). ↩

-

An example of this are the demands and dialogues organised by the pottery women of Quinchamalí, that together with the Chilean Ministry of the Cultures, Arts and Heritage, requested to be included on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding of Unesco. ↩

-

Haesbaert, Rogério, « Del Mito de La Desterritorialización a La Multiterritorialidad », in Cultura y Representaciones Sociales, vol. 8, n°15, 2013, pp. 9-42. ↩

-

See: [online] https://www.boyaca.gov.co/ecuador-apropio-la-campana-mas- bra-menos-plastico/ ↩